A few years ago, divers discovered an apparent underwater “lost city” off the coast of Zakynthos in Greece. New research reveals that the site, which was thought to be the ruins of a long-forgotten civilization that perished when tsunamis hit the shore, is in actuality a geological formation—and a bizarre one at that.

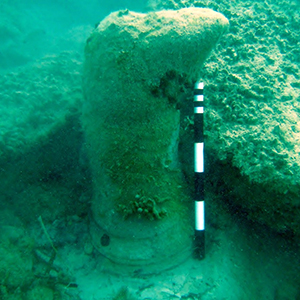

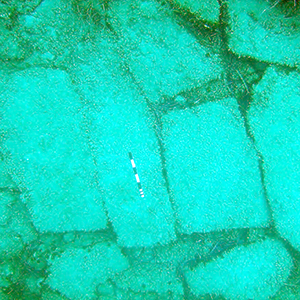

Looking at the photos of these underwater formations, it’s hard to blame the divers for coming up with their initial assessment. These things look wholly unnatural, resembling paved floors, moorings, courtyards, and colonnades.

“The site was discovered by snorkelers and first thought to be an ancient city port, lost to the sea,” said study lead author Julian Andrews from the University of East Anglia. “There were what superficially looked like circular column bases, and paved floors. But mysteriously no other signs of life—such as pottery.”

Well, it was too good to be true. It now appears that this “lost city” never really existed. Researchers from UEA, along with experts from the Department of Geology and Geoenvironment at the University of Athens, recently conducted a mineralogical and chemical analysis of various formations found at the site. In particular, they investigated the mineral content and texture of the underwater formations using microscopy, X-ray, and stable isotope techniques.

“We investigated the site, which is between two and five meters under water, and found that it is actually a natural geologically occurring phenomenon,” said Andrews.

The researchers found that the linear spread of the cement-like structures is likely the result of a subsurface fault which never ruptured the surface of the sea bed. This fault allowed gases, including methane, to seep up from deep below the Earth’s surface.

“Microbes in the sediment use the carbon in methane as fuel. Microbe-driven oxidation of the methane then changes the chemistry of the sediment forming a kind of natural cement, known to geologists as concretion,” explained Andrews. “In this case the cement was an unusual mineral called dolomite which rarely forms in seawater, but can be quite common in microbe-rich sediments. These concretions were then exhumed by erosion to be exposed on the seabed today.”

The strange formations were created up to five million years ago, and are quite rare in such shallow waters. Similar structures, say the researchers, tend to be hundreds and often thousands of meters deep underwater.

Originally posted by George Dvorsky on Gizmodo.com